Ancient Ireland's Mysterious Tombs

About a half-mile past the entrance to Newgrange, in the Valley of the Boyne, County Meath, Ireland, is a handmade sign with an arrow that reads "Irish crafts for sale." I am, of course, fascinated by Newgrange, a Neolithic site that predates Stonehenge by a thousand years, but I can never pass up yarn, so I turned into a modest farm, damp, green, full of sheep, well-used equipment and warning signs - "This is not a playground."In the shop, Allison, the owner, was at the spinning machine, and of course I did buy a sweater, hand-knit, pale green cable, for my granddaughter, and also a Christmas tree ornament that looks like a sheep. We chatted about Allison's flock (170 of them), their breed (hornless Irish Belclare), the problem with horned sheep (Daisy, for example, though hornless, is inconveniently dominating, always trying to give the other ewes a poke).

Boyne Valley Wools Craft Shop, Located less than a 5 minute walk from the Brú na Bóinne visitor centre.

I drove away and turned into the parking lot at Newgrange, but the farm cast an interesting glow over the ancient but beautifully rebuilt site - this is a place long inhabited, where passing observations of sunlight, rain, animal interactions, the growth of the rich greenery, how lives must or might be lived flicker in the atmosphere like sparkles of mist.

I steered my rental car between lovely metalwork gates that reproduce the style of the Neolithic engravings at Newgrange, which looks like a huge green beret set neatly onto a green hillside in a gently rolling landscape.

Newgrange is a popular destination, and tickets are first come first served. It is called a "passage mound" or "passage tomb," but what is it really? If we are lucky, what we get when we visit an ancient site is a sense of the intelligence that designed and built the structure even if we might not understand what belief system they were acting under. Indeed, perhaps Newgrange is a giant calendar, a giant clock, a giant belief system, built without mortar, lost and present at the same time. This time of year, Newgrange takes on a special significance when the site becomes mysteriously aligned with the rising sun at the winter solstice, flooding its interior with an almost mystical light.

It is 338 feet in diameter, slightly larger than the circumference of the outer ring at Stonehenge. The white quartz stones that make up the outer wall were brought here from Wicklow (71 miles south) and the granite cobbles from Rathcor (40 miles north). The stones I saw are a reproduction of the original. Ninety-seven larger boulders, known as kerbstones, averaging three tons apiece, were brought from a site on the Irish Sea about 19 miles to the north, but even if they were floated on boats all the way to this spot, they would still have had to be dragged about a half-mile up the hill from the River Boyne to the monument. The underlying stone structure is hidden by a smooth, slightly flattened and peaceful-looking grassy lawn.

This was my second visit in two days, there was much to see, and the line was short - there were maybe 10 of us waiting. My turn came, and I climbed the outer stairs, then went down into the entryway. The stone in front of the entrance is a large oval that has been carefully incised with carved connecting spirals.

Newgrange features a facade adorned with white quartz stones, creating a striking and reflective surface

Perhaps more unique is the "roofbox" - something like an open window set onto the heavy lintel stone that defines the doorway. The two people who went before me came out, and I entered the passage. Like many ancient passages, it wasn't built for tall women like me. Heavy stone slabs lean inward; it is a tight corridor; I felt as if I was walking slightly down hill. There was a little light, and I avoided bumping my head, but I could hardly see the interior engravings. At the bottom of the path, it was difficult to gauge how far I'd come.

There was nothing grand about the passage until I got to the bottom, and turned around. The guide told us what to look at. And then, the demonstration - how, for 17 minutes on the morning of the winter solstice, and only then, the sun shines through the roofbox, down the passage right to the bottom, right to what might be some sort of altar with a basin sitting on it. Someone outside shone an electric light through the roofbox (which was discovered in 1963), demonstrating the effect. I imagined the miracle of such a thing, total darkness pierced so precisely by sunlight. The tools used to build the monument were made entirely of stone, bone and wood.

Later, I drove to the mouth of the River Boyne, on the Irish Sea, 31 miles north of the River Liffey, which flows through Dublin. The landscape is flat, and, this day, a little damp and gloomy. The shingle beach, edged by wild green plants of all types, stretches toward a broad estuary. Even to me, the river seemed to promise an easy and productive trip inland. It is evident why countless men in ships accepted the invitation - in 2013 a boat made of logs, possibly 5,500 years old with "a pair of oval shaped blisters on the upper edge" indicating oars, according to reports, was found near Drogheda, not far from where a dredging operation in 2006 revealed a Viking ship.

At the mouth of the Boyne, there are two Neolithic standing stones (mythologized as a cow and her beloved calf). I crossed the river in Drogheda, a medieval town five miles inland. Since I grew up beside the mile-wide Mississippi, known in St. Louis as "The Big Muddy," the River Boyne reminded me more of a creek (as it passes through Drogheda, it is 140 feet wide), but it is deep, full of fish, easily navigable, just the sort of river that spawns civilizations.

The River Boyne loops south from County Louth into County Meath about three miles west of Drogheda, and inside this loop, there are more than 40 prehistoric sites, set on hilltops, and visible one from another. One of the special pleasures of Newgrange and the Valley of the Boyne is the sense of history, deep history, as something rural rather than urban. Drogheda was founded by the Normans toward the end of the 12th century. I stayed at a bed-and-breakfast south of town, near the giant tanks of a local dairy, and drove through the countryside from one site to another.

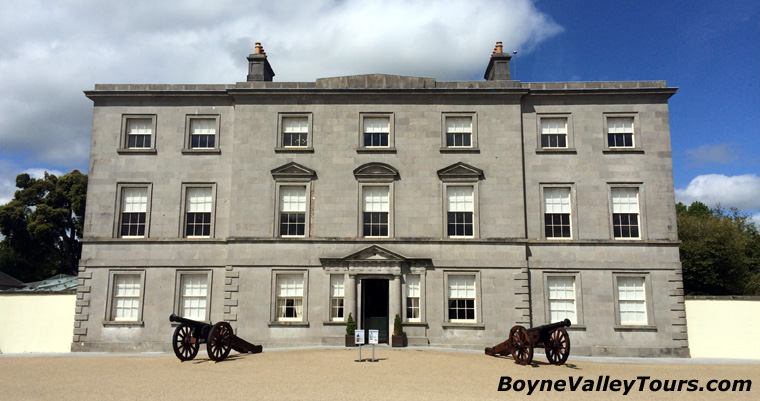

The biggest battle in Irish history was the Battle of the Boyne, fought just west of Drogheda in 1690 between King James II of England, who had been deposed and was attempting to regain his kingdom, and William of Orange, the Dutch choice of English Protestants. James had 23,000 troops and William had 36,000. William won, reinforcing and entrenching the conquest of Ireland by the English. The museum dedicated to the Battle of the Boyne - an elegantly refurbished 1740 early Palladian-syle mansion that looks out over a vast and very green set of fields just where William's troops crossed the river and attacked James's - was completed in 2008.

The Battle of the Boyne was significant to the rediscovery of Newgrange, which had been ignored or used as a source for building materials, because a follower of William of Orange, Charles Campbell, took over the property. Campbell, too, saw the monument as a pile of building material, but when his laborers removed some of the stones, they discovered the entrance to what they assumed was a cave.

The first person to become curious about what really made up the mound was a Welsh naturalist, Edward Lhwyd (pronounced "Lloyd"), a friend of Isaac Newton. Lloyd, well known for precision, wrote four letters about Newgrange, in 1699 and 1700, detailing what he saw as the mound was excavated. Campbell himself also explored the site, and he reported to a later visitor, Sir Thomas Molyneux, that the bones of two complete corpses had been found, a man and a woman. Lhwyd didn't report the human remains, but they were uncovered in 1967, when modern archaeologists were excavating the site. The skeletons were a bit of a conundrum - Molyneux speculated in a published 1726 account that they were the remains of a prominent man and his wife, a la Akhenaten and Nefertiti.

At least 15 antiquarians visited the mound at Newgrange in the 200 years between Molyneux and the first truly modern investigator, George Coffey, who visited in the 1890s and again in 1912. All were perplexed by the origins of the mound, and none of them thought that ancient Irish inhabitants could have been capable of building such a structure.

Undoubtedly, this was because the Valley of the Boyne is deep inside "the Pale" - the area of Ireland that came under the control of the English in the mid-12th century. A ditch and rampart that enclosed parts of Louth, Meath, Dublin and Kildare defined "the Pale" and cut English-based scholars off from Celtic literature and history. But the Old Irish literature of invaders from the east was well aware that the Celts had been preceded by a group that they called the Tuatha De Danann.

I kept driving. The roads are narrow, neatly hedged. Sometimes the valley is open and scenic; other times the trees seem to close in. To the northeast there is Dowth, the smallest, least well-known of the passage tombs and, from the road, the most private of the three sites - over the top of the hedgerow, I could see the passage mound bulging green and uneven, the absolute emblem of mysterious privacy.

Two mounds have been discovered, but the site has not been rebuilt. A narrow series of roads runs from there past farmhouses and fields of black and white cows, past Newgrange again. The view of Newgrange up the hill from the road was beautiful; the view from Newgrange was rolling, green, utterly quiet.

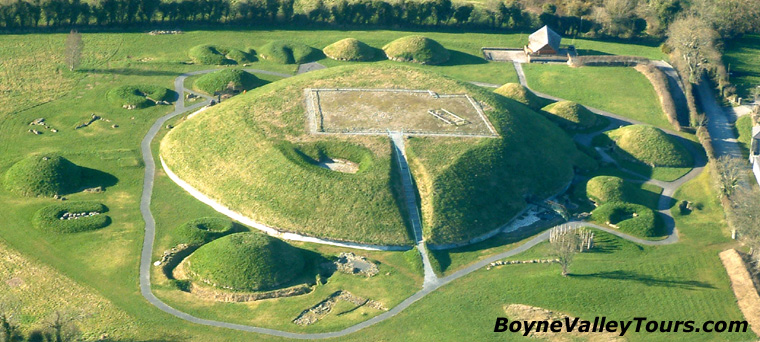

Knowth may be the most elaborate and historically well-used assembly of tombs - 18 in all - and passages. Knowth was, perhaps, more important in its day than Newgrange. Excavation here began in the late 1960s, and was immediately productive. In a 2008 article in The Irish Times, the archaeologist George Eogan recalled crawling up the eastern passage (there is also a western passage), carrying a light, and coming to a "void" at the end. He said, "In my great excitement I jumped down six or seven feet, and to my amazement I found that what I had jumped into was a massive cruciform ('cross-shaped') chamber. There was an astonishing amount of art and a magnificent stone basin in the right-hand recess." Mr. Eogan's group has also found evidence of pottery, houses and flint from 4000 B.C., in addition to finds from the same period as Newgrange.

Knowth is more irregular in appearance than Newgrange, but at least as impressive. And there is plenty of evidence that post-Neolithic inhabitants of the area were aware of, and made use of, the facilities at Knowth - one of the oddest remains is graffiti on the stones in the passages from between A.D. 700 and 750, when the area was resettled and the passages were used as living quarters.

"It's amazing when you come across the inscriptions, there's something about them that brings you face to face with people," a scholar from University College, Dublin, Francis J. Byrne, told The Irish Times in 2008. "If you met them, you would probably be telling them off, don't be desecrating this monument." Investigation into the complexities of Knowth and how it has been repurposed over the last 6,000 years is continuing.

Experts are beginning to agree that Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth once served as astronomical monuments, noting their level of sophistication. Archaeologists rejected these ideas as fantasies for a long time, interpreting the orientation of the passages at Newgrange and Knowth as coincidental and the incised stones as a set of meaningless geometric designs.

In his 2012 book, Newgrange, Monument to Immortality, the Drogheda journalist and novelist Anthony Murphy points out that Neolithic farmers would have had many reasons to pay attention to weather, seasons and the passage of time. He also observes that they would be much more likely to pay close attention to the moon and the stars than we do, with our electric lights and internet data. He considers Newgrange and Knowth epic calendars that measured years, leap years and other temporal cycles.

I widened my range a little - there was so much to see, both in terms of landscape and of historical structures. In Monasterboice, six miles north of the river, there is a circular tower and a crowded graveyard containing the oldest known Celtic cross, still in beautiful condition.

Not far from Collon - four miles from Monasterboice - are the remains of an enormous abbey from the 12th century (Old Mellifont), simultaneously neat, airy and spooky.

There are towns (Donore, Navan) and castles (Trim, from the Norman period, and Slane, reconstructed in the 18th century, now the site of big rock concerts). There is Drogheda itself.

But Newgrange is the beginning - DNA analysis and archaeological evidence indicate that farming in the region began somewhere around 4500 B.C. It may have been that farmers from the Middle East came up the river in those log boats, discovered the unusual fertility of the valley (a result of the last ice age) and encountered an entrenched indigenous population. But there are no signs of a conflict; either the Neolithic farmers mixed peacefully with the Mesolithic foragers, or the foragers themselves imported agriculture, took those log boats to the east and returned. It was the farmers, having cleared the land and harvested their crops, who had the leisure time to build one passage tomb after another, Mr. Murphy suggested.

Archaeologists and investigators are not finished in the Valley of the Boyne. Many things are waiting to be discovered, put together, understood. As I looked across the rich green flow of the hills toward the setting sun, I expected to come back to this mystery.

Newgrange and the Valley of the Boyne are north and west of Dublin - driving a car to Drogheda takes between 30 and 40 minutes, and the bus takes about 50 minutes. Drogheda is about halfway between Dublin airport and the border of Northern Ireland. There are tours to the Neolithic sites, but the freedom of roaming the Valley of the Boyne is inspiring, too.

Newgrange has a modern and very informative visitors' center, which should not be missed.

The Battle of the Boyne Visitors Center, also informative, is in a renovated building, with a wonderful view over the valley, and a beautiful formal garden, as well as a restaurant and a gift shop.

Based on an article by Jane Smiley printed in the New York Times on December 25th 2016.

Private Driver Day Tour

to Newgrange the UNESCO World Heritage site, the Hill of Tara a Celtic Royal site, Monasterboice 10th

century round tower and high crosses and the Hill of Slane where St. Patrick lit the Paschal Fire

in the 5th century. Personalised service with collection at your hotel or cruise ship by Sedan or

Mercedes MPV in the Dublin / Meath / Louth area. Airport collection or drop off can be included as part of the tour.

Private Driver Day Tour

to Newgrange the UNESCO World Heritage site, the Hill of Tara a Celtic Royal site, Monasterboice 10th

century round tower and high crosses and the Hill of Slane where St. Patrick lit the Paschal Fire

in the 5th century. Personalised service with collection at your hotel or cruise ship by Sedan or

Mercedes MPV in the Dublin / Meath / Louth area. Airport collection or drop off can be included as part of the tour.

Take a suggested tour of the Boyne Valley or we can collaborate with you to design a custom Boyne Valley Day Tour.

Book a Private Day Tour

Boyne Valley Tours Privacy, Terms and Conditions

Boyne Valley Tours Privacy, Terms and Conditions

Home

| Private Driver Tour

| Cruise Excursion

| Places

| Ireland's Ancient East

| About Us

| FAQs

| Contact

| Newgrange

| Knowth

| Hill of Tara

| Monasterboice

| Trim Castle

| Mellifont Abbey

| Slane